UPDATE: A new Information kit – Collaborative Process on the Second-Generation Cut-Off has been added to the additional information/documents section (2024-03-19)

I am pleased to announce that we have completed the Membership tab on the MCK website. The membership tab will explain the role and responsibility of the Indian Registration Administrator, the legislation surrounding Indian Status for section 11 bands and how Indian Status in determined. To help facilitate members who live far from the territory or who work strict hours the renewal forms, guarantor declarations and new registration forms can all be found on the website. You can now renew your own status cards should you wish to do so. I hope you will find the new website helpful, useful, and informative.

Best Regards

Amanda Simon

Indian Registration Administrator

Table of Contents

1. WHAT IS AN INDIAN REGISTRATION ADMINISTRATOR

2. WHAT TO DO IF A STATUS CARD IS LOST, STOLEN, DAMAGED OR DESTROYED

3. WHEN YOU REPORT YOUR STATUS CARD LOST, STOLEN, DAMAGED OR DESTROYED

4. IMPORTANT NOTICE TO SERVICE PROVIDERS

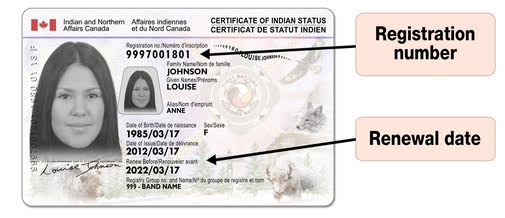

5. WHICH STATUS CARDS ARE CURRENTLY BEING ISSUED AND ARE CURRENTLY IN CIRCULATION? THESE ARE THE ONLY CARDS THAT SHOULD BE ACCEPTED BY MERCHANTS.

6. SECURE CERTIFICATE OF INDIAN STATUS

7. CERTIFICATE OF INDIAN STATUS

8. ARE OLDER VERSIONS OF THE STATUS CARD STILL VALID

9. HISTORY OF THE STATUS CARD

10. ADDITIONAL INFORMATION/ATTACHMENTS

11. FORMS

12. BACKGROUND – THE INDIAN ACT

13. SECTION 11 OF THE INDIAN ACT

All information below can be found on the Indigenous Services Canada Website, link below. All information below is accurate as of April 2022.

What is an Indian Registration Administrator

An Indian Registration Administrator (IRA) is a band employee on reserve who does work related to the administration of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) programs.

IRAs are delegated specific authorities by the Indian Registrar. The roles of IRAs vary from band to band. By working at the band level on behalf of ISC, IRAs are able to maintain the Indian Register and help band members apply for Indian status and status cards.

According to section 5 of the Indian Act, ISC is responsible for the Indian Register as well as band lists maintained at INAC.

A current, up-to-date, and accurate Indian Register is needed to deliver ISC programs and services as it identifies who is entitled to participate in certain programs.

IRAs issue certificates of Indian status. As of June 2016, the certificate of Indian status is issued by some 500 Indian Registration Administrators located in band offices across the country.

What to do if a status card is lost, stolen, damaged or destroyed

If you’ve lost your Secure Certificate of Indian Status or if it has been stolen, damaged or destroyed, please report the incident by calling Public enquiries.

REPORT YOU LOST OR STOLEN STATUS CARD BY CALLING 1-800-567-9604 OR BY EMAIL: aadnc.infopubs.aandc@canada.ca – Reporting you lost or stolen status card is your responsibility. Please protect yourself against identity theft and fraudulent use of your status card.

The call agent will:

- cancel the lost, stolen, damaged or destroyed card to make sure it won’t be used for fraudulent purposes

- issue, if requested, a Temporary Confirmation of Registration Document

PLEASE CALL AMANDA SIMON, INDIAN REGISTRATION ADMINSTRATOR AT THE MOHAWK COUNCIL OF KANEHSATAKE AT 450-479-7011 OR BY EMAIL AT simon.amanda@kanesatake.ca to request your temporary registration document. Requests by walk-in at the Band Office will not be accepted.

The replacement process is the same as when first applying for a secure status card. Fill out the same form and check “Replacement (lost, stolen, damaged SCIS)” under “Reason for application”.

If you’ve lost your Certificate of Indian Status or if it has been stolen, damaged or destroyed, contact your First Nation office to apply for a replacement.

When you report your status card lost, stolen, damaged or destroyed

Your 10-digit registration number doesn’t change when you are issued a new status card.

IMPORTANT NOTICE TO SERVICE PROVIDERS:

Not all indigenous people in Canada are eligible for a status card. The Inuit and Métis do not have status cards because they are not an “Indian” as defined by the Indian Act — at least not yet. In the case of Daniels v. Canada, the Federal Court recognized them as “Indians” under the Constitution. Status Cards obtained by purchase are not valid. These cards all constitute fraud.

ACCEPTING ANY OTHER FORM OF INDIAN STATUS OTHER THAN THE EXAMPLES HEREUNDER CONSTITUTE FRAUD.

Which status cards are currently being issued and are currently in circulation? These are the only cards that should be accepted by merchants.

The Secure Certificate of Indian Status and the Certificate of Indian Status are currently being issued to confirm registration under the Indian Act.

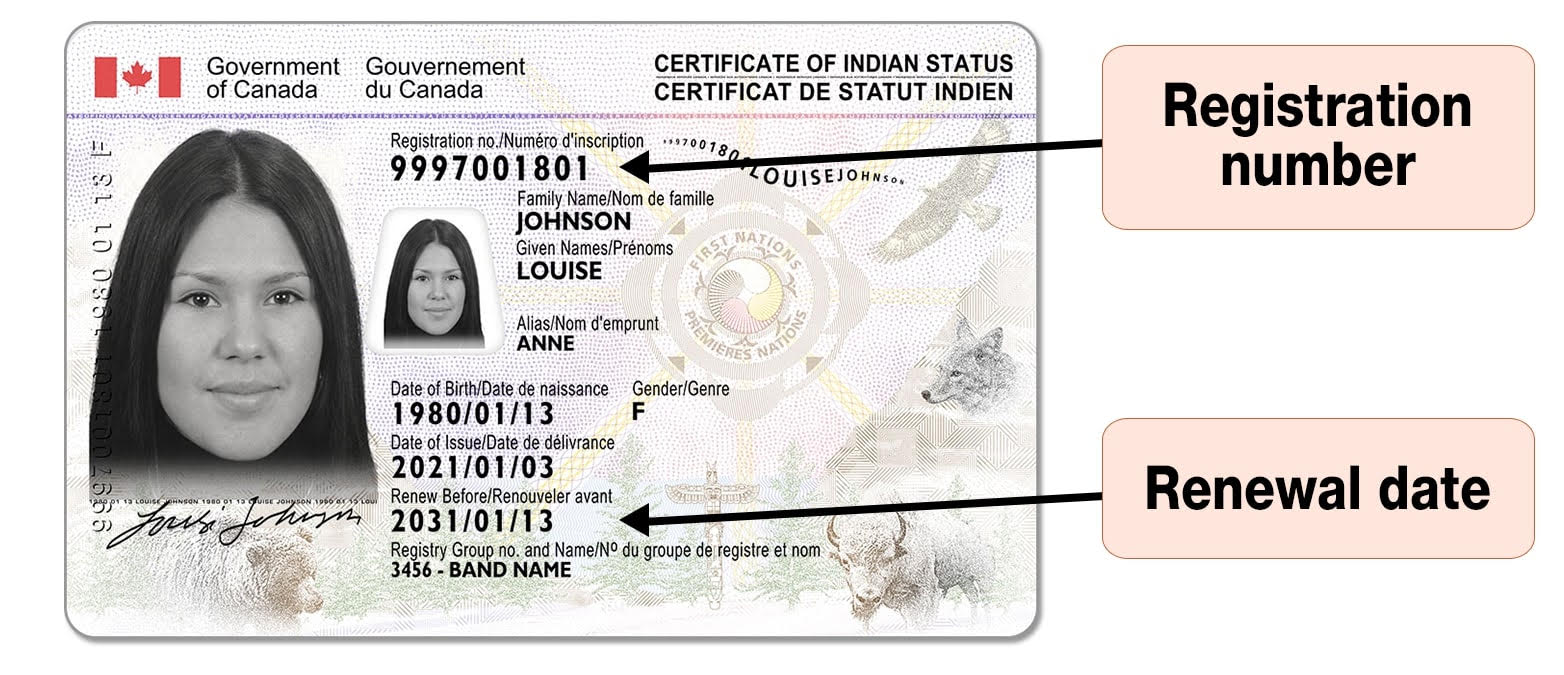

Secure Certificate of Indian Status

The Secure Certificate of Indian Status, or secure status card, issued centrally by ISC, has a number of security features:

- laser-engraved information burned directly into the card

- raised letters and numbers on the surface

- patterns of extremely fine lines not easily scanned or copied

- ultra-violet imaging and printing visible with special equipment

- secondary photo image of the cardholder visible from both sides of the card

- toll-free number to call to confirm card is valid

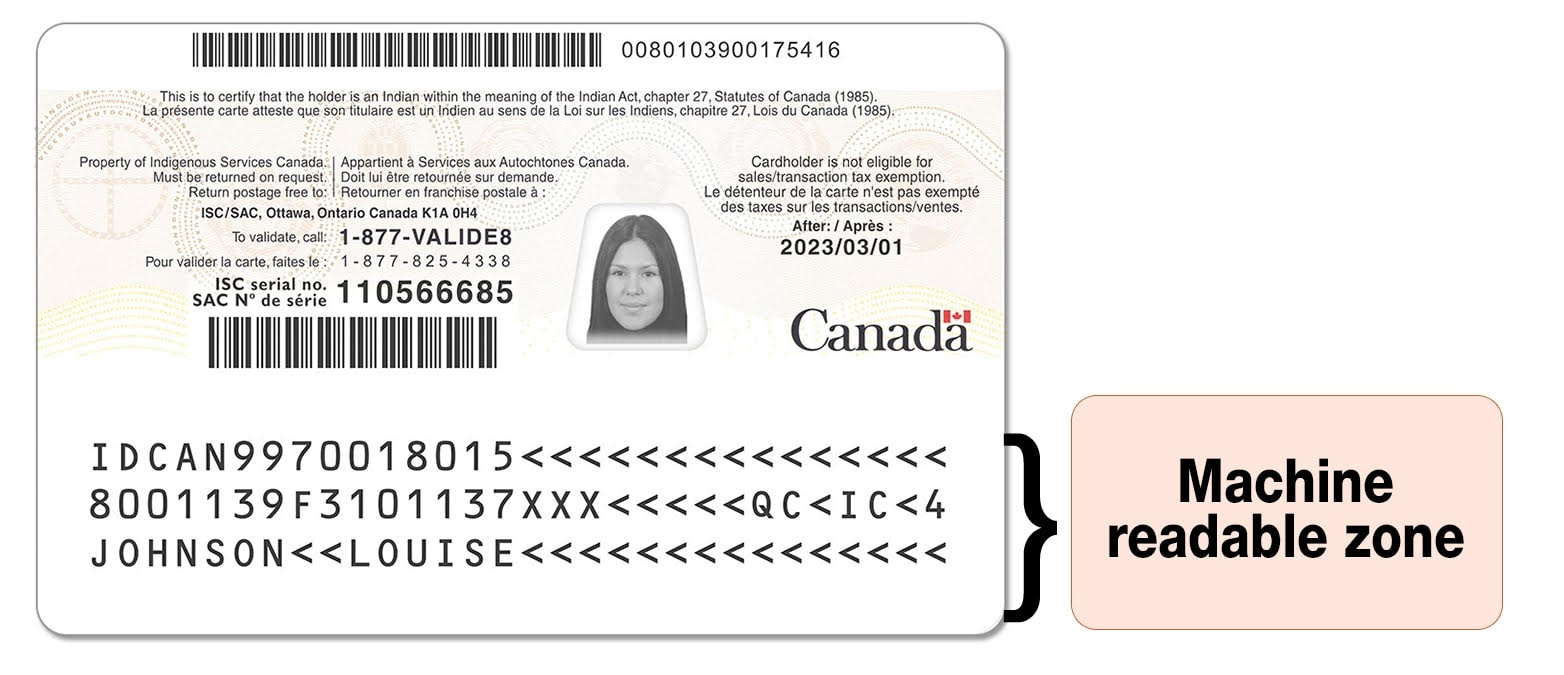

- machine-readable zone to facilitate Canada–U.S. border crossing

As of February 1, 2019, all new and renewed secure status cards are issued with a machine-readable zone on the back of the card.

The machine-readable zone contains only cardholder information that is already displayed on the front of the card.

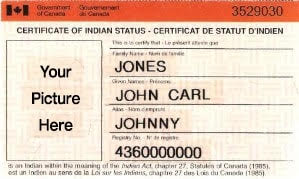

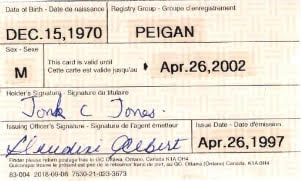

Certificate of Indian Status

The Certificate of Indian Status, or status card, is still issued in some band offices. This card has only a limited number of security features found on other government-issued identity documents.

CERTIFICATES OF INDIAN STATUS ARE NO LONGER ISSUED IN KANEHSATAKE, PLEASE ENSURE YOU APPLY FOR YOU SECURE STATUS CARD.

The laminated status card with no renewal date is also still valid.

If your status card is no longer valid, you may be denied benefits and rights for Indigenous peoples or have difficulty crossing the Canada–U.S. border.

History of the status card

In 1956, the Government of Canada began issuing the Certificate of Indian Status, or status card, as an official identity document confirming the cardholder to be registered under the Indian Act.

The status card is either a laminated or a plastic card with fewer security features than now expected of a government-issued identity document.

In 2009, a more secure status card, the Secure Certificate of Indian Status, began to be issued it help protect Status Indians from identity theft. Improved security features make it less vulnerable to tampering and counterfeiting.

Status Indians are encouraged to apply for a secure status card.

For people wanting to get registered to Indian Registry through recent legislation such as C-31 and C-3 please seek your genealogy at the following link. Research is your responsibility and not that of the Indian Registration Administrator.

For people wanting to get registered to Indian Registry. Please seek help in find your genealogy at:

Genealogy and Family History – Library and Archives Canada (bac-lac.gc.ca)

Additional Information/Attachments

Forms

NOTICE: PLEASE RIGHT CLICK ON THE LINKS BELOW AND SELECT SAVE LINK AS IN ORDER TO ACCESS THE FORMS

AS WITH ANY FORMS THAT REQUIRE A GUARANTOR, ENSURE THEY SIGN COPIES OF YOUR IDENTIFICATION

REGISTRATION AND SECURE CERTIFICATE OF INDIAN STATUS (SCIS) GUARANTOR DECLARATION

Information Kit – Collaborative Process on Second-Gen Cut-Off and S10 Voting Thresholds

BACKGROUND – THE INDIAN ACT

The definition of Indian in colonial legislation (1850 to 1867) was broad based, mostly sex neutral and focused on family, social and tribal or nation ties. While the term Indian was often interpreted broadly, the authority to determine who was an Indian shifted to government control beginning in 1869. The Gradual Enfranchisement Act in 1869 and the first Indian Act in 1876 introduced a narrower definition of an Indian. Over the years, amendments to the Indian Act have significantly changed the ways in which entitlement and band membership are determined.

KEY DATES AND AMENDMENTS TO THE ACT

This chapter will discuss the most significant changes made to the Indian Act which occurred in

1876, 1951, 1985, 2011, 2017 and most recently in 2019.

1876 – The Indian Act

- At this time, male lineage was emphasized and the first reference to illegitimate children was introduced.

- an illegitimate child is defined as a child born to parents who are not married to each other at the time of the child’s birth, or out of wedlock.

- The introduction of loss of band membership because of foreign residency for a period of over 5 years without permission of the Superintendent General was introduced.

- Indian status was denied to individuals who had taken scrip.

o Scrip is defined as a certificate offered to persons of mixed Indian ancestry primarily in the Northwest Territories and Prairie Provinces (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba) as a one-time payment in money or land in exchange for their aboriginal rights in and to the land. People who took scrip were not entitled to treaty rights.

- Any Indian by virtue of their education and profession was now automatically enfranchised.

I.e. lawyers, doctors, priests, teachers, etc.

o Enfranchisement is defined as a process by which an Indian gave up status and band membership (voluntary or involuntary).

1951 – An Act Respecting Indians

The 1951 Indian Act set out rules for determining Indian status in much greater detail. The 1951 legislation contained provisions for the following:

- The Indian Register was created as a centralized record of all persons entitled to registration, commonly known as the Black Register, named for the colour of binders in which the records are stored. The Indian Registrar was appointed and today remains the sole authority in the determination of which individuals shall be added to and deleted or omitted from the Indian Register and band lists.

- Individuals and band councils now had the right to protest additions or deletions and omissions from the Indian Register.

- Illegitimate male children of Indian males could be registered.

- The illegitimate child of an Indian woman was registered unless it was established that the father of the child was not an Indian.

- An Indian was eligible for enfranchisement by meeting certain criteria. These included the ability to assume the responsibilities of citizenship and to support himself and his family

(Voluntary enfranchisement).

- A woman who had lost her status by marrying a non-Indian could be enfranchised

(Voluntary or involuntary).

1956 – An Act to Amend the Indian Act

The 1956 amendment to the Indian Act legislation contained the following key change:

- The registration of illegitimate children was now permitted without an investigation into paternity but if a protest was made regarding the paternity of a registered child and confirmation of non-Indian paternity was established, the child’s name would be removed from the Indian Register and the Band List.

1985 – Bill C-31 – An Act to Amend the Indian Act

In 1985 the Indian Act was amended again to be brought in accordance with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Bill C-31, as it is known, came into force on April 17, 1985.

The Bill was introduced keeping three principles in mind.

- Remove gender-based discrimination from theIndian Act;

- Restore Indian status and band membership rights within the meaning of theIndian Act to those who had lost them under discriminatory provisions of the past;

- Give Indian bands the right to control their own membership.

1985 – Bill C-31 – An Act to Amend the Indian Act continued:

The new provisions of the Indian Act under Bill C-31 had a major impact on entitlement. The most significant changes were as follows:

- Women no longer gain or lose their entitlement to registration because of marriage.

- The practice of enfranchisement is abolished.

- The marriage of parents is no longer to be a factor in the entitlement of children.

With the passing of Bill S-3 in 2019, the parents’ marriage is now one of two key criteria that impacts whether an individual is entitled to registration.

- First Nations and Bands can now choose to control their own membership (S.10 vs. S.11).

- Eligibility for registration is significantly changed from previous legislation.

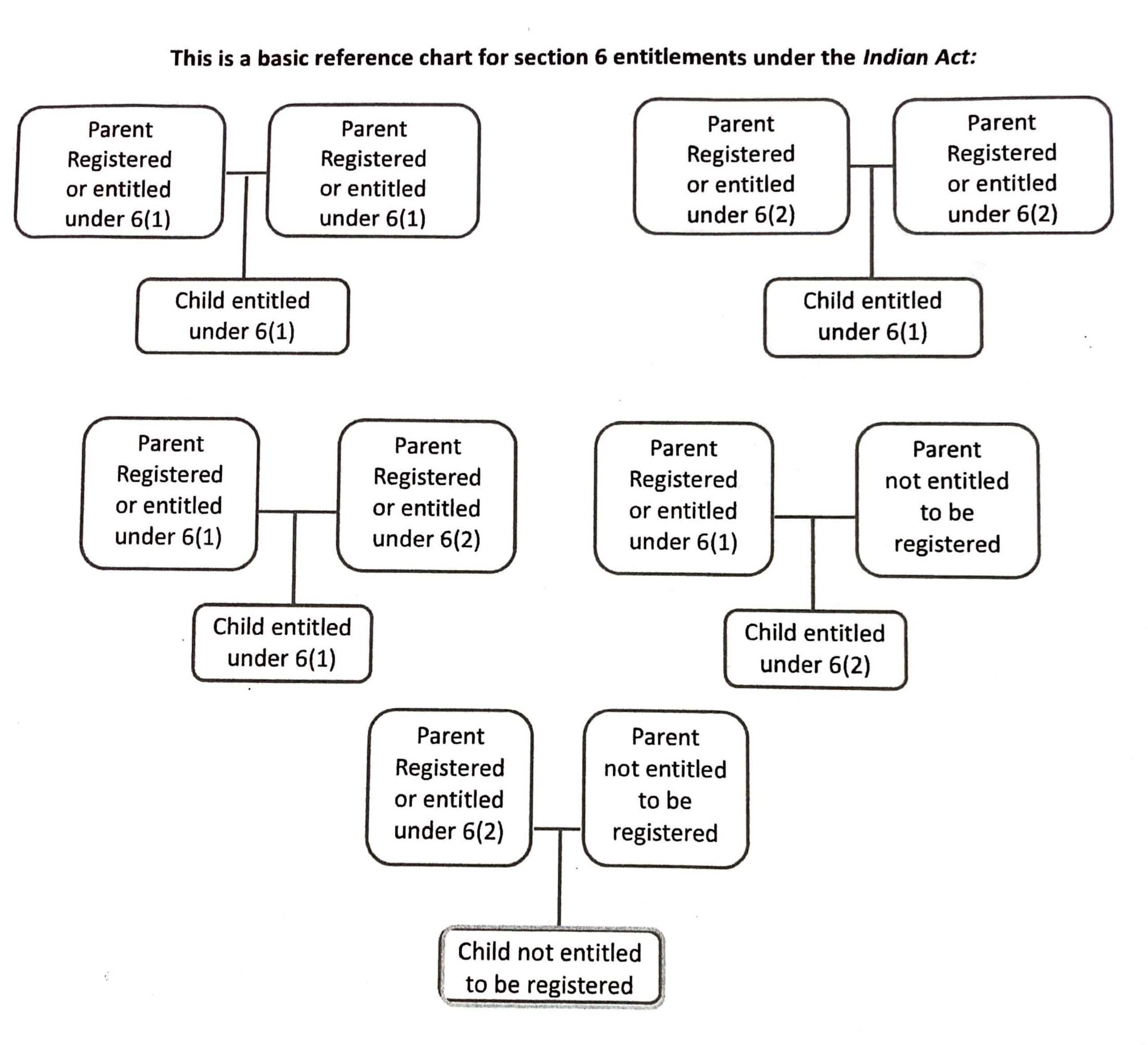

Bill C-31 resulted in 7 new entitlement categories under Section 6 of the Indian Act.

| Entitlement Category | Rationale |

| 6(1)(a) | Persons who qualified under any of the previous versions of the Indian Act and who did not lose that entitlement before the 1985 amendments. *Prior to April 17, 1985, non-Indian women could gain Indian status upon marriage to a male Indian. For this to happen, the husband had to be registered or entitled to be registered since birth, in accordance with paragraph 6(1)(a) of the Indian Act. |

| 6(1)(b) | Persons who are members of groups declared to be new bands by the Governor in Council. |

| 6(1)(c) | Restoration of Indian status to:

|

15 GCDOCS # 58937364

| Entitlement | Category Rationale |

| 6(1)(d) | Restoration of Indian status to:

*A wife who had no status prior to her marriage to an enfranchised Indian is only eligible if it is established that she is entitled in her own right. |

| 6(1)(e) | Restoration of Indian status to:

|

| 6(1)(f) | Persons born prior to April 17, 1985, who have no entitlement under any other provision of subsection 6(1) of the Act and whose parents are both entitled to registration as Indians.

Persons born on or after April 17, 1985, whose parents are both registered or entitled to be registered as Indians. |

| 6(2) | Persons who have one parent who is registered or entitled to be registered in accordance with subsection 6(1) of the Indian Act.

Second Generation cut-off: Any person who has one parent registered or entitled to be registered under subsection 6(2) and, whose other parent is a non-Indian, is not entitled to be registered as an Indian. |

16 GCDOCS # 58937364

2011 – Bill C-3 – The Gender Equity in the Indian Registration Act (GEIRA)

The 2011 amendments to the Indian Act were incited by a civil lawsuit filed by Sharon McIvor and her son Jacob Grismer. In 2009, the Court of Appeal for British Columbia ruled that the Indian Act discriminates between men and women, and therefore violates the equality provision of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The passing of Bill C-3 resulted in one new entitlement category under Section 6 of the Indian Act, allowing for status to be passed to eligible grandchildren of women who had lost status on marriage to a non-Indian.

6(1)(c.1)

Following the passing of Bill C-3, people who were previously denied may be newly entitled under subsection 6(2) of the Indian Act if they meet all the following criteria:

- Their grandmother lost her status or is deemed to have lost her status because of marrying a non-Indian prior to April 17, 1985.

- One of their parents is registered or entitled to be registered under subsection (6)(2) of the Indian Act.

- They or one of their siblings is born on or after September 4, 1951.

With Bill S-3 coming into full force in August 2019, this is no longer a criterion.

2017 – Bill S-3 – An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général)

As Bill C-3 failed to fully eradicate inequities in Indian registration, legal action was brought forth by Stephane Descheneaux and Susan Yantha in 2011. They argued that amendments to the Indian Act under the 2011 Gender Equity in Indian Registration Act (Bill C-3) did not go far enough in addressing sex-based inequities in Indian registration. On August 3, 2015, the Superior Court of Quebec declared that key provisions, 6(1)(a), (c), and (f) and subsection 6(2) of the Indian Act unjustifiably violated equality rights by perpetuating sex-based inequities in eligibility for Indian registration between descendants of the male and female lines.

In July 2016, the Government of Canada launched its approach to respond to the Descheneaux decision by the Superior Court of Quebec.

2017 – Bill S-3 – An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général) continued

The approach included two phases:

- Legislative changes to immediately amend theIndian Act through Bill S-3 (Phase 1): An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of Quebec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général).

- Collaborative process on Indian registration, membership and First Nation citizenship.

2017 – Bill S-3 – Phase 1 – Immediate legislative amendments came into force on December 22, 2017 and addressed the following:

- Issues raised in Descheneaux: Cousin’s issue and Siblings issue.

o Cousin’s issue relates to the differential treatment in how Indian status is gained and passed on among first cousins dependent on the sex of the Indian grandparent.

o Siblings issue relates to the differential treatment of illegitimate male and female children (siblings born out of wedlock) born to an Indian father between the 1951 and 1985 amendments to the Indian Act.

- Omitted minor’s issue.

o Relates to the differential treatment of minor children born to an Indian mother, who were recorded on a First Nation or band list and who lost entitlement to Indian status, between September 4, 1951, and April 17, 1985, as they were minors at the time of their mother’s marriage to a non-Indian.

- Issues raised in the Gehl court case: unknown or unstated parentage.

- Other identified sex-based issues.

Bill S-3 Phase 1 resulted in the addition of 7 new entitlement categories under Section 6 of the Indian Act, however, under Bill S-3 phase 2 (2019) these categories are no longer applied.

- 6(1)(c.01) Addresses the child who lost status upon their mother’s marriage to a non-Indian.

- 6(1)(c.02) Addresses the child removed as a result of a protest due to non-Indian paternity and children affected by the double-mother clause.

- 6(1)(c.2) Extension of 6(1)(c.1).

- 6(1)(c.3) Addresses the illegitimate female child of an Indian male.

- 6(1)(c.4) Extension of 6(1)(c.2) and (c.3)

- 6(1)(c.5) Extension of 6(1)(c.4)

- 6(1)(c.6) Extension of 6(1)(c.02) only applies to individuals whose parent was “removed by protest” under subsection 12(2) of the Indian Act.

18 GCDOCS # 58937364

2019 – Bill S-3 – Phase 2 – An Act to amend the Indian Act in response to the Superior Court of

Québec decision in Descheneaux c. Canada (Procureur général)

Bill S-3 came into full force on August 15, 2019, also known as Phase 2 of Bill S-3.

These amendments address the following:

- All remaining known sex-based inequities in Indian Registration dating back to 1869, the date of the Gradual Enfranchisement Act.

- The removal of the 1951 cut-off date.

o The removal of the 1951 cut-off ensures that all descendants born prior to April 17, 1985 (or of a marriage before that date) of women who lost status or were removed from lists because of their marriage to a non-Indian man going back to 1869 will now be entitled to registration.

Bill S-3 coming into full force resulted in the following changes under Section 6 of the

Indian Act:

- The renumbering of two pre-existing entitlement categories.

o 6(1)(c) renumbered to 6(1)(a.1)

o 6(1)(c.3) renumbered to 6(1)(a.2)

- The addition of one new category.

o 6(1)(a.3)

- The repeal of 7 categories.

o Repeal of all 6(1)(c)’s.

**As of August 15, 2019, there are no remaining 6(1)(c)’s in the Indian Act.**

This is a basic reference chart for section 6 entitlements under the Indian Act:

SECTION 7 – PERSONS NOT ENTITLED TO BE REGISTERED

There are two types of non-entitlements.

- Legislated non-entitlements, and

- Non-entitlements based on ancestry.

Section 7 of the Indian Act refers to legislated non-entitlements.

7(1)a: refers to non-Indian women who gained status through marriage (prior to April 17, 1985) and subsequently lost that status, are not entitled to be registered unless they had an entitlement to status prior to their marriage, or now have an entitlement.

7(1)b: refers to the child of a non-Indian woman who gained status only through her marriage to the Indian man is not entitled to status if that child’s father is not an Indian.

SECTION 10 AND 11 – FIRST NATION AND BAND MEMBERSHIP

Historically, registration under the Indian Act usually carried with it an automatic entitlement to band membership. In 1985 the amendments to the Indian Act (Bill C-31) separated Indian Registration from membership.

There are 3 different types of First Nation Membership defined within the Indian Act.

- Section 10

- Section 11

- Self-Governing First Nations

Section 10 of the Indian Act – Band Control of Membership

A section 10 First Nation or Band controls its own membership list and sets its own eligibility requirements. Section 10 of the Indian Act sets out the requirements to assume control of its membership list and transfer the department’s responsibility for that list to the First Nation or Band.

- Upon registration if an individual is affiliated with a Section 10 band the individual must apply directly to the band for membership.

Section 11 of the Indian Act – Membership Rules for Departmental Band Lists

Section 11 First Nation and Band lists are maintained by the Department. The membership rules are found in Section 11 of the Indian Act.

Upon registration, if an individual is affiliated with a section 11 First Nation or Band, their name is automatically added to the list.

KANEHSATAKE IS A SECTION 11 BAND.

Bill S-3: Eliminating known sex-based inequities in registration (sac-isc.gc.ca)

FOR ALREADY REGISTERED MEMBERS PLEASE USE THE APPROPRIATE FORM. REMEMBER THAT A GUARANTOR DECLARATION IS NECESSARY WITH ALL SCIS APPLICATIONS. ENSURE THAT YOUR GUARANTOR SIGNS YOUR PASSPORT SIZED PHOTOGRAPHS, YOUR COLOR PHOTOCOPIES OF 2 PIECES OF IDENTIFICATION SUCH AS DRIVERS LICENSE AND MEDICAL CARD. (IN THE ABSENCE OF A DRIVERS LICENSE ANOTHER FORM OR IDENTIFICATION WITH YOUR CIVIC ADDRESS CAN BE USED. YOU CAN ALSO COPY A UTILITY BILL WHICH PROVES YOUR CIVIC ADDRESS). NEW REGISTRATION REQUIRE AN ORIGINAL CIVIL STATUS BRITH CERTIFICATE AND THE USUAL IDENTIFICATION OF THE REGISTERING PARENT.

Amanda Simon

Amanda Simon was employed by Belgo International, Amacan Maritime, Terran Shipping, and finally opening her own computer business. Amanda has gained over 25 years varied commercial and industrial experience, firstly as an employee, in progressively increasing responsible positions and more recently as a business woman and Entrepreneur of First Nation Computers Inc., founded in 1998. The success of the business was highlighted with Indian Affairs publication of a video called “A Striking force” and later with a year long run on the APTN network filmed by Tshinanu.tv. Amanda applied and was awarded the position of Lands Manager with the Mohawk Council of Kanehsatake in April 2009, and immediately began her first year of study with the University of Saskatchewan Indigenous Peoples Management program and graduated in June 2010. She continued her study with NALMA PLMCP program and later graduated in April of 2011. In 2013 she was accepted to Ryerson University obtaining a Certificate in Public Administration and Governance. As a Certified Lands and Estates Manager, Amanda continues her training with 7 core courses per year.